Coffee: From Bean to Brew

- Hadia Mawlawi

- Oct 28, 2021

- 8 min read

Updated: Oct 28, 2021

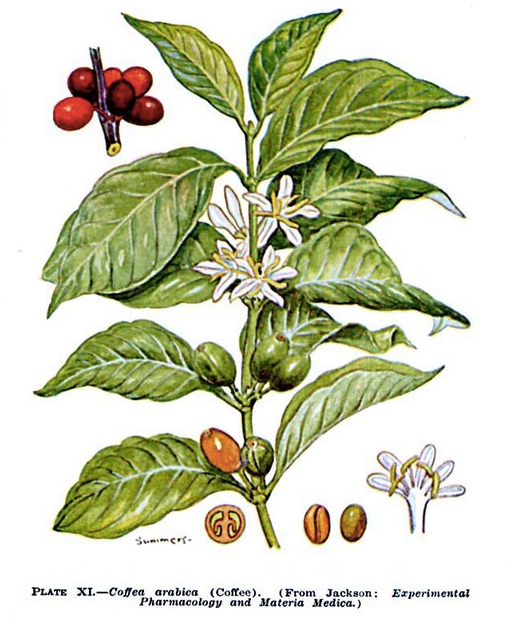

Goats, monks, cherries. These are not the first words you would associate with a morning cup of coffee. Yet legend has it that the origin of coffee comes from forests on the Ethiopian plateaus where in the ninth century, a goat-herder noticed his goats were energized after eating a type of berry from a local coffee tree. A similar observation was made when monks in a local monastery stayed alert through the long hours of evening prayer after consuming these same berries, as a fruit rather than a beverage. Word spread of these energizing berries and by the 1400s Coffea arabica made its way east to the Arabian peninsula in modern-day Yemen, and by the 1600s, to the rest of the world.

photo credit: https://sca.coffee/research/coffee-plants-of-the-world

Today coffee is widely consumed but few consumers stop to consider where the beans come from, how many varieties exist, how they are picked, processed or brewed. They just know that coffee tastes good, is an easy stimulant and an essential part of their day.

In this post, I will give an overview of coffee, from bean to brew, including a tasting I had at Mio Brew in Houston under the attentive guidance of master cupper Felipe Paz.

Arabica and Robusta

The two most common coffee trees are Coffea arabica and Coffea canephora, more commonly referred to as Robusta. There are over 120 other different species but these are the two grown in largest quantity. Arabica is the better of the two, yielding higher quality coffee and making up 60% of the world's annual coffee production. It also prefers temperatures of 64-71 degrees Fahrenheit, making it increasingly susceptible to global warming. Robusta on the other hand originated at lower levels in West and Central Africa, able to withstand temperatures of up to 78 degrees Fahrenheit. All the world coffee grows between the Tropic of Capricorn and the Tropic of Cancer. Click here to see this geographic region.

photo credit: https://www.plantgrower.org/coffee-arabic.html

Once or twice a year (as in Colombia) the strongly scented blossoms of coffee appear after a long period of rainfall. Because the Arabica is self-pollinating, its flower will always yield fruit.

The coffee fruit

Coffee beans are actually green seeds from a piece of fruit known as a coffee cherry, the familiar name given to the fruit of the coffee plant. The coffee cherry is a type of stone fruit (drupe) that is usually red in color when fully ripe. Inside each cherry fruit are two green seeds, which are the coffee beans used to make coffee.

photo credit: https://elevencoffees.com/what-is-a-coffee-cherry/

Coffee seeds are extracted from their silver skin and parchment to reveal the bean we roast, grind and brew.

photo credit: https://elevencoffees.com/what-is-a-coffee-cherry/

On the whole, the size of the coffee fruit is the size of a small grape but most of its volume is taken up by the central seed, with only a thin layer of fruit flesh (mucilage) under the skin.

The skin is usually a deep red when ripe, and ripeness is tied to the quantity of sugar in the fruit which is vitally important when trying to grow delicious coffee.

Processing

After the harvest, (picking the fruit from the trees) the coffee cherries are taken to a wet mill to separate the beans from the flesh and dry the beans so they are safe for storage. There are four distinct processing methods all of which change the sweetness, body and acidity of brewed coffee : Natural (also referred to as dry-processed), washed, wet-hulled and honey-processed.

Known as dry process, this is the oldest method and is used in countries where water is scarce. Beans are dried to approximately 11% moisture to properly prepare them for storage. When done right, natural coffees result in heavy-bodied cups of coffees with deeper and more complex tasting notes, due to the way the seeds dry with the full cherry still intact. They are also juicy and syrupy.

Depulper machines remove the seeds from the ripe cherries before drying them. Once the skin and pulp is removed from the seed, the seed goes into a tank full of water to remove the pulp and mucilage (fruit) before going onto beds to dry in the sun. Washed processed coffee have cleaner, more crisp tasting notes, unlike the natural processed coffee. The body of a brewed washed-processed coffee is lighter. Typically, there is also more brightness because of a cleaner acidity that balances out the sweetness of the coffee.

Also called semi-washed processing, this process is common in Indonesia. Rather than move to drying beds, the cherries get stored in plastic tanks. The mucilage also remains on the seeds, and much moisture is retained. The mucilage creates a thick husk that encapsulates the seeds and go through a process called hulling to remove it before laying out flat to dry. Drying time is half of the other processing and the coffee is dried to a moisture content of 30-35% rather than 11% . The taste of a wet-hulled coffee is heavy-bodied thanks to the dried mucilage, but it is also chocolatey, savory and nutty.

This method involves a combination of both the natural and washed methods. It is a less commonly practiced method but yields a unique cup of coffee. The amount of mucilage (fruit pulp) left on the seed is what determines the sweetness before the seed is set out to dry on a bed. Flavors are varied and complex but mostly sweet with a pronounced acidity. Remember, acidity in coffee is a good thing. Bitterness is not! Acidity adds depth and complexity to the coffee and is the result of microbial reaction of the yeast and bacteria that break down the sugars in the mucilage, producing the acids.

Next time you buy your bag of beans you may be curious to ask what processing method was used and how this alters the taste of your brew.

For an overview of the 12 steps of making coffee click here.

To read about the roasting process read this article.

Tasting the coffee

After the bean is dried, milled, and roasted, it's time to test the coffee for quality and taste. This process is referred to as cupping.

I participated in a coffee tasting in a newly opened coffee bar in Houston, Mio Brew. The owner, Felipe Paz, set up a counter with three varieties of coffee to taste: Colombian (Huila region), Ugandan & Colombian (Pacific Winds).

He explained that usually a tasting has five cups of the same coffee to evaluate for defects and profile. In this tasting, only three cups were evaluated because we were starting with clean cups.

Here are the steps to taste and evaluate coffee as per The National Coffee Association (NCA):

First, the taster — usually called the cupper — evaluates the beans for their overall visual quality. The beans are then roasted in a small laboratory roaster, immediately ground and infused in boiling water with carefully-controlled temperature. The cupper noses the brew to experience its aroma, an essential step in judging the coffee's quality.

photo credit: Hadia Mawlawi

After letting the coffee rest for several minutes, the cupper breaks the crust by pushing aside the grounds at the top of the cup. Again, the coffee is nosed before the tasting begins.

photo credit: Hadia Mawlawi

To taste the coffee, the cupper slurps a spoonful with a quick inhalation. The objective is to spray the coffee evenly over the cupper's taste buds, and then weigh it on the tongue before spitting it out. Slurping aerates the coffee in the mouth! This means it is being sufficiently spread across the palate and allows the nasal taste receptors to help out. For more on this process read here.

The language used to describe the coffee reminded me of the breadth and range of words used to describe wine- These included terroir, dark chocolate, woody, floral, acidity, and balance (of flavor & acidity). The distinctions in flavor are caused by the variety of the plant, chemistry of the soil, weather (amount of rainfall and sunshine) and altitude, combined with the processing method.

Here are some lessons learned from Felipe during the tasting:

The first thing you do when assessing a cup of coffee is smell- aroma is key in identifying taste.

There is the fragrance right after grinding, the aromas which escape right after water hits the ground coffee, and the flavors (defined here as a combination of taste and smell) that hit the palate when the coffee is sipped. Tasting coffee is a sensory experience and needs a lot of practice to develop the palate and gain experience with the lexicon.

Felipe suggests to be guided by your first impressions. Do you detect notes of berries? citrus? oak/ wood? There is a tool in the market to help you with finding the right sensory lexicon to match your experience- It is called Le Nez du Cafe: https://www.lenez.com/en/kits/coffee/revelation

For a less pricey alternative there is the coffee taster's flavor wheel:

The National Coffee Association developed a cupping form to evaluate sensory characteristics and quality in coffee- The sheet includes scores for fragrance/ aroma, acidity, body, uniformity, and whether it is a clean cup (free faults and defects).

Articulating flavor is one of the hardest things to do. I know if I like or dislike a particular taste but trying to give it a word is a whole other mastery. There is no substitute for practice, and mindful tasting rather than speedy slurping, and asking questions like: Is it nutty? Does it taste sweet, bitter or acidy? Is this coffee fruity? if yes, berry or citrus-like? The tasting wheel is a very handy tool to help guide you in identifying tastes more accurately: keep one handy next time you are tasting coffee.

Brewing

Brewing coffee is an art. I realized this during my tasting at Mio Brew. Everything matters: the quality of the bean, the freshness of the coffee, how recently the coffee has been grinded, the way the coffee has been stored, the water you use. I learned that for optimal extraction of flavor, the water temperature to brew coffee is between 195-202 degrees Fahrenheit. When pouring water over the ground beans, it makes a big difference to use a gooseneck kettle and to pour water slowly, waiting 30 seconds in between pours to allow the carbon dioxide from the beans to escape and the bed of coffee to swell and expand (the bloom). The gooseneck kettle also allows for a more even pour, controlling saturation of the coffee.

photo credit: https://www.craftcoffeeguru.com/gooseneck-kettle/

For an in-depth look at the world of brewing, click here

Today we are in the fifth development wave of coffee- The term refers to a period in time or stage in the coffee industry. These waves represent big changes in the industry and also the changes in the global culture brought by coffee itself.

photo credit: https://www.allegraceoforum.com/what-is-the-5th-wave/

Here's an overview of each of the waves:

1st wave (1900s): Coffee becomes a commodity and its consumption grows exponentially

2nd wave (1990s): American coffee giant Starbucks transforms coffee culture

3rd wave (2000s): coffee starts being purchased based on its production origin and its method of production.

4th wave (2010s): Coffee is a direct and fair trade with a direct re-investment to specific farmers and their families. It is a partnership from source to sip and back to the source.

5th wave (mid 2010s): Greater influence from high-quality boutique chains adopting a more advanced set of business practices and delivering well-crafted artisan product at scale.

I hope you enjoyed reading this post and will walk away a little more aware of the complexity that hides behind each cup of coffee. I was intrigued, and my interest deepened following the tasting session and the additional reading I did. I still have a lot of curiosity about capsules versus fresh grind, differences in origin, the world of brewing, light versus dark roast, milk versus none at all. Perhaps I will tackle these topics in a future post. For now, I will enjoy the fresh coffee I bought from Mio Brew and encourage you to venture out and make a new bean selection next time you need to replenish your coffee supply. There is no shortage of choice.

Further reading:

The World Atlas of Coffee: James Hoffmann

Uncommon Grounds: Mark Pendergrast

Comments